Issue:

Martin Charlton lurks into the murky world of espionage and discovers the inspiration behind John Buchan's famous novel

The beaches were deserted. Only the locals and a few determined holidaymakers remained as war cast its shadow over Europe. The Kaiser’s troops had failed to withdraw from neutral Belgium and Britain was now at war with Germany. It was 4 August, 1914.

A few days earlier, Broadstairs beaches had been packed with the usual holiday crowd, determined not to let the crisis in Europe spoil their fun. Now there was the threat of German naval bombardment of the coastal towns, and a desire from the nation’s men and boys to show their loyalty to king and country. The fun was over as the country entered one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century.

The British had been fighting an imaginary war with Germany since the early 1870s. The country was seen as both an economic and military threat and jingoistic propaganda speculating about German intentions had been circulating in books and the press. One such was the Erskine Childers 1903 novel The Riddle of the Sands, which foretold of German preparations for an invasion of England.

Such scaremongering extended to the younger generation, with similar stories appearing in boys’ magazines and comics – one ran a rip-roaring yarn of the ‘evil Hun’ invading Kent, only to be thwarted by a gallant troop of Boy Scouts. There were also rumours of enemy spies, and it is alleged that a German agent was captured at North Foreland.

One of those determined holidaymakers that August was a Scottish author, John Buchan, and Broadstairs would be influential in the development of his most famous novel, The Thirty-Nine Steps.

The Buchan family came to Broadstairs – little changed since the time of Charles Dickens – Ion doctor’s orders. Sea air had been prescribed for their six-year-old daughter, Alice, who was recovering from a mastoid operation. Taking rooms at St Ronan’s guesthouse, 71 Stone Road (now demolished), Susan Buchan later wrote:

We had some quite nice lodgings at the seaside and should have enjoyed ourselves, as Alice’s health improved all the time, but the war precluded all happiness and comfort…

It wasn’t just the war – literally days old – that blighted their holiday. Shortly after arriving, intense stomach pains seized Buchan. Bored and bedridden, he began working on an idea for a ‘shocker’ –his name for thrillers – apparently at Susan’s suggestion.

In fact, he had been toying with the notion of writing a detective story for some time. ‘I should like to write a story of this sort,’ he told his wife. ‘And take real pains with it. Most detective story-writers don’t take half enough trouble with their characters, and no-one cares what becomes of either corpse or murderer.’

Also in Thanet at the same time were Susan’s cousin, Hilda Grenfell, and her family. They were renting a cliff-top villa half a mile away at North Foreland which had a set of steps cut into the chalk that led down to a private beach. The villa was called St Cuby and is believed to be the inspiration for Trafalgar Lodge, where the book’s hero, Richard Hannay, meets the villainous Mr Appleton.

However, it was the steps that most caught Buchan’s imagination. Back then there were 78 wooden steps, which zigzagged through two shafts and three tunnel sections. As is still the case today, the upper entrance was surrounded by bushes that, as in the novel, obscured the passage from view, while the beach entrance was accessible only at low tide.

Today, more than a century of erosion has done away with most of the beach. The wooden steps were replaced in the 1940s with more than 100 concrete ones, which are now crumbling, and signs at both ends state that public access is prohibited. Inside, a rusting handrail leads up and the remnants of light fittings can be seen in the tunnel sections. Even so, if you stop and let your imagination take over, you can almost hear the frantic footsteps as one of Appleton’s spies tries to make his escape: ‘Schnell, Franz,’ cried a voice, ‘das Boot, das Boot!’

Buchan continued his convalescence at St Cuby and, as his health improved, he started to get acquainted with the town and the surrounding area. With the holiday crowd gone, Broadstairs was just a quiet little seaside town – the perfect spot for enemy spies to leave the country, with the Continent 20 miles across the Channel.

Another factor in the story’s development was the public’s fear that German spies operated throughout the country. On Friday 28 August – two days after Buchan’s birthday, which he celebrated at St Cuby – the Thanet Times ran a spy scare story in which a Margate woman found herself confronted by two men, one armed with a revolver. ‘The men told her to keep quiet, because they were after German spies,’ the paper reported.

The gun turned out to be a toy and, when questioned by police, the men explained how they had witnessed suspicious activity at a local garage. They had stopped the woman, believing her to be involved. It is quite feasible that, even if Buchan didn’t read about himself, he could have heard about it through local gossip.

In the autumn of 1914 and now back in London, Buchan tried to enlist in the army, but was rejected on the grounds of age and health. He continued to suffer with the stomach pains, then diagnosed as a duodenal ulcer, and was instructed by his doctor to rest if he was to avoid an operation.

However, being a workaholic, he kept busy and, when not writing his thrillers, which he did for relaxation, he was absorbed by war work. This resulted in The Thirty-Nine Steps being written in bits and pieces over the next few months. It was serialised in Blackwood’s Magazine between July and September 1915 and Blackwood & Sons published it in book form in October of that year.

The action starts in London, although most of the story is set in Buchan’s native Scotland. However, in the last chapter, Various Parties Converging on the Sea, the finale takes place in the fictional town of Bradgate – inspired by Broadstairs.

No one is certain how he came up with Bradgate. Some believe that it was taken from the Saxon words ‘brad’ (meaning ‘broad’) and ‘gaet’ (‘access to the sea’). Another theory is that he simply took the ‘Brad’ from Bradstowe, a little hamlet now part of the town, and ‘gate’ from nearby Kingsgate. One more suggestion is that Bradgate was an ancient name for Broadstairs, but there is no hard evidence for this.

The chapter opens with Hannay (based on a young army officer Buchan had met while serving as the private secretary to the High Commissioner in South Africa, some ten years earlier) ‘. . . looking from the Griffin Hotel over a smooth sea to the lightship on the Cock sands . . .’

There were two hotels in Broadstairs during 1914. The Grand – now converted into private flats – sits on the clifftop, overlooking Louisa Bay, and is unlikely to be Hannay’s hotel. The view described in the novel best matches that from the Royal Albion Hotel, although you can’t see the Goodwin Sands, undoubtedly the inspiration for ‘Cock sands’, from here. However, the sands and the North Goodwin Lightship could easily be seen, on a clear day, from Broadstairs pier.

After breakfast, Hannay and Scaife, a British agent, walk along the beach to check out the lower entrance of the steps, before heading for ‘the Ruff’ where they keep watch on Trafalgar Lodge. Buchan’s description of the Ruff matches nicely with that of North Foreland: ‘. . . I had a view of the line of turf along the clifftop, with seats placed at intervals, and the little square plots, railed in and planted with bushes, whence the staircases descended to the beach’. While keeping watch on Trafalgar Lodge, Hannay mentions seeing a man on a bike with a set of golf clubs, clearly on his way back from Kingsgate golf course.

At the end of the day, though, one question remains – why 39 steps? Again, there are a few theories. As already mentioned, there were 78 wooden steps in 1914. One theory is that a friend suggested he should halve that number to 39, because it would make a better title. Another states that Buchan could stride these steps two at a time, which again gives us 39, although he would have had to be in better health to do this. It is also worth noting that he celebrated his 39th birthday while staying in Broadstairs.

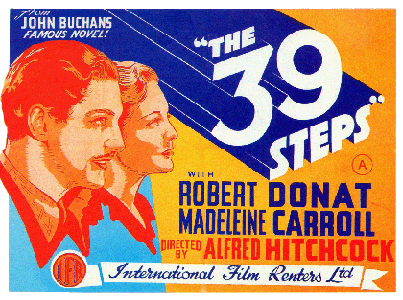

Since it was first published in 1915, Buchan’s book has never been out of print, and has been adapted for film three times and at least once for television. Alfred Hitchcock directed the first in 1935 and also borrowed heavily from the novel when he made North by Northwest in 1959 – Cary Grant’s character too finds himself caught up in the sinister world of espionage when he is mistaken for the nonexistent George Kaplan.

Hitchcock was not the only person whose work was influenced by The Thirty-Nine Steps. When it was first published, one of its readers was a young Ian Fleming, who would go on to create the most famous fictional spy, James Bond.

Although John Buchan clearly had the idea to write another story before his holiday, if he hadn’t come to Broadstairs, been taken ill and later seen the underground staircase at North Foreland, we might not have The Thirty-Nine Steps. Quite a sobering thought when you consider what else we may have missed . . .